- Historical background

Delphine Saint-Martin: First of all, thank you again for this interview, let us start with an introductory question on the South China Sea dispute, on the reasons for the dispute and the States that are involved; historically, what are the claims of these States in this region?

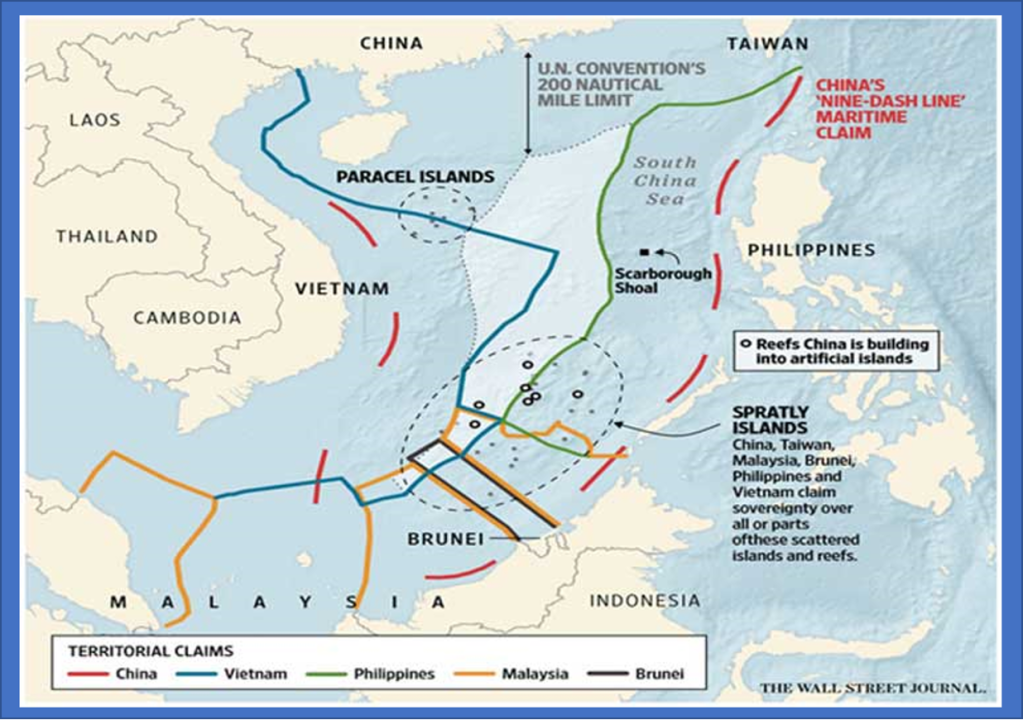

Pierre Thévenin: The States involved in the dispute are China, Taiwan, Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei, Singapour, Malaysia, and Vietnam (see map 1). The South China Sea dispute is wider than the South China Sea case. The case only involved the Philippines and China. Regarding the issue of the sea as a whole, in fact, the problem began after WWII.

Historic overview:

- In 1877, English merchants exploited the islands to collect guano.

- In the 1920s until WWII, France claimed sovereignty over the Spratlys (and Paracels).

- During WWII, Japan claimed sovereignty over the islands.

- After the war, by virtue of Peace treaties between Japan and the Allies Nations, and between Japan and the Republic of China, Japan relinquished over the islands.

Before WWII, France then Japan were sovereign on the Spratly Islands and Paracels islands. The former is a group of islands south of the China sea, in front of the Philippines and Indonesia (see map 2). The latter are in front of China’s mainland and Vietnam (see maps 1 and 2).

When WWII started, Japan took sovereignty from France over the Spratly Islands and Paracels Islands. But when they were defeated and signed a treaty’s treaty with the Allied Forces and with China, Japan ceded sovereignty over these islands, but they did not name who would be sovereign in their place. So up until now there is no clear sovereign States upon these islands. It is not written anywhere in a treaty who is sovereign over the Spratly Islands and Paracels Islands. This is one part of the problem.

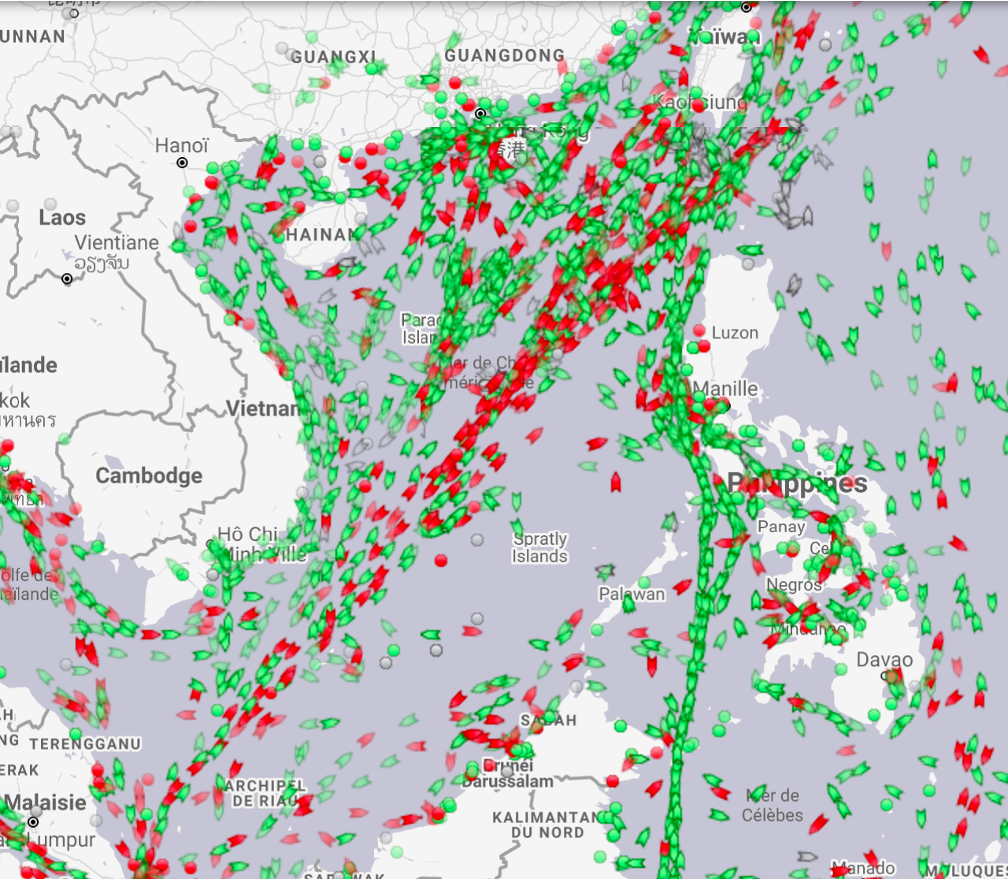

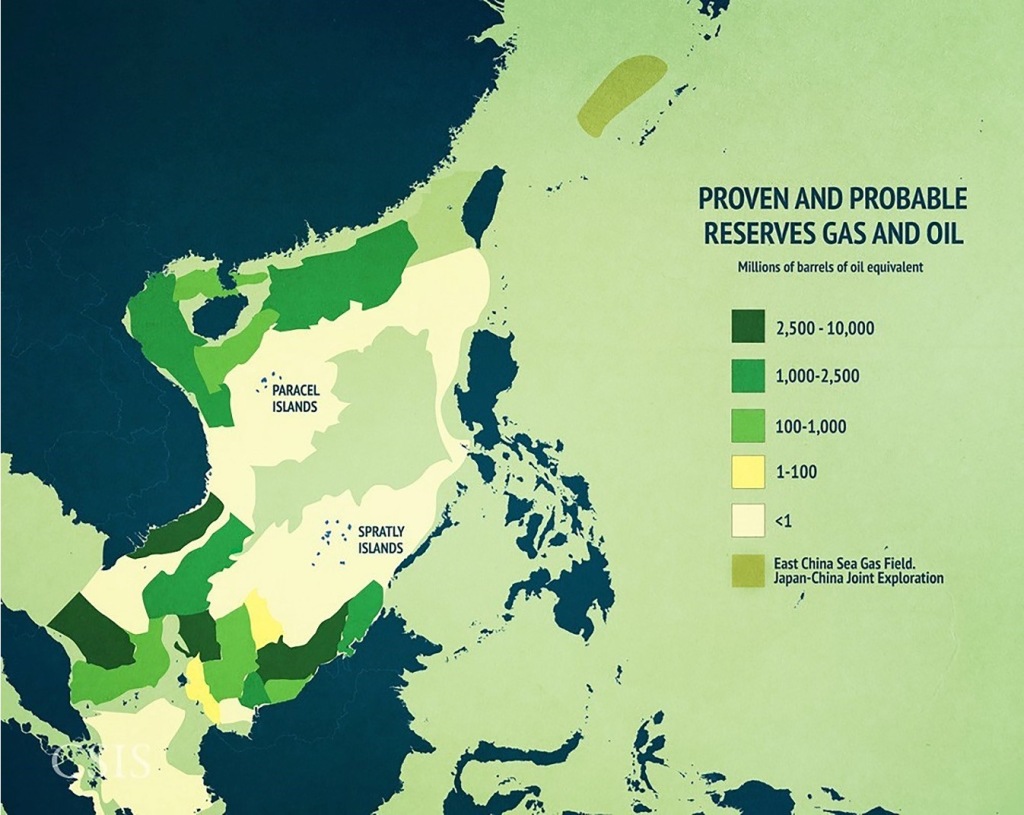

The second part of the problem (see map 4), the South China Sea is important in terms of maritime traffic and oil. The South China Sea is very rich in oil and gas reserves (see map 6). There is an interest for the States to control the region to control the maritime traffic in this sea (see map 4) and to have access of the resources, to gain control over them and to have the right to exploit them. The main issue is the right to exploit the fish resources and oil. To do that, you need to have control over the biggest maritime expanses possible, so you need to have control over the island. This is because international law claims over sea expanses can only stem from the fact that you possess, that you are sovereign upon land territory. That is why the Spratly Islands and to a lesser extent the Paracels Islands are so important. This is the crucial point of the whole dispute, to have sovereignty over these islands. The second question which is interesting: are the Spratly Islands in fact islands?

Delphine Saint-Martin: On the historical rights, do the other states also have historical rights going as far back as the 12th century?

Pierre Thévenin: So far only China has this claim so we do not know really as far as others are concerned. Although, it is not surprising that China can actually make the claim because it had an hegemony over the region for a long time. Plus, international law as we know today was built by European nations, it does not mean that there did not exist any international law standards in other parts of the world before. Here I am referring to “Tannaccas’ ‘ book, “Transcivilizational Law”. What he shows in this book says that, in fact, there were some kind of legal relations in South East Asia and actually China was the hegemon of the region. So all states were vassals of China and they paid respect to the Chinese emperor. So it is actually understandable why other coastal states did not make a claim, because in history since China was a hegemon, they could more easily build a claim. In addition, China was a maritime power, much more than other States, and richer than the others, they were in capacity to have a decent fleet, which others might not have been able to do.

Delphine Saint-Martin: We can see that the history of China, their claims, and their use of the region have influenced their claims nowadays on the sovereignty of the region.

Pierre Thévenin: Comparing the claims in map 2 and map 3, we can see that every coastal state has claims, but these do not match. Under international law, coastal states can claim up to 200 nautical miles of Exclusive Economic Zone, to have sovereign rights over living and nonliving resources (fish and oil). But in fact, almost no participants claiming part of the South China Sea are doing so in conformity with international law, it is the case especially for the main participants which are Vietnam, China, and the Philippines.

The construction of artificial islands is not contrary to international law in some circumstances. However, since most of the artificial islands built by China (see picture 1) are in the Philippines’ EEZ, it is not in conformity with the Convention on the Law of the Sea. Besides they are built for military purposes, which is not in conformity with international law as the sea should be used exclusively for peaceful purposes. This also raises concerns from China’s neighbours.

Regarding the US, the South China dispute is contained within the wider American and Chinese relations but historically the Americans always defended the freedom of navigation. So, the Americans use their navy in what they call FONOPs (Freedom of Navigation of Operations) and in the contested areas in areas where coastal state denies access to certain parts of the sea, they will use their navy and sails across the sea to show that the seas are free and there is universal freedom of navigation so, that is their main interest in the South China Sea, except monitoring Chinese expansion.

Most importantly the Arbitral Tribunal has said that China was not sovereign upon the Spratly Islands because there was nothing to be sovereign over, since the islands are not islands but in fact rocks, it is not possible to be sovereign over this. You can not claim sovereignty over a rock. You are sovereign over a rock if it is in proximity of your coast, otherwise you can not make sovereignty claims over a rock. That is why the nine-dash line falls short of the sovereignty claim because there is nothing to claim sovereignty over.

Delphine Saint-Martin: To continue on this historical background, you talked about this China claim of the nine-dash historical claim, could you elaborate on this claim and the history of the different countries in the area and their different claims with the history related to fishing and other practices?

Pierre Thévenin: China has made a claim about the nine-dash line quite recently, if we talk about the dispute. Because, in fact, after WWII, there is no sovereignty that is declared upon the islands, so it is terra nullius, in terms of law, the islands do not belong to anyone. So there is a competition between States, among which there is China. In order to assert its sovereignty over the islands, China claims that it has a nine-dash line claim (see maps 1, 2 and 3). The nine-dash line is a historical thesis. China claims that it is sovereign upon all the seas and lands contained in the nine-dash line, for historical reasons. It claims that it has sovereignty since the 12th century, China used to sail and fish in the area, and to exert some kind of control over the area. So they argue that since the 12th century, they are sovereign upon the area, so every island contained within the nine-dash line should be theirs. But they have revived the theory of the nine-dash only recently. So they have worked a bit backwards: they needed to assert their sovereignty over the islands since the end of WWII and they devised an argument saying that they were sovereign upon South China Sea and the islands way before, for nine centuries they were sovereign upon it. So for China is arguing that for several centuries they have exercised rights, so given all of their history, the islands should be theirs.

Vietnam had commerce in the region, they used to fish. In recorded history, at least what can be found in English speaking sources and western archives, Vietnam used to use the sea and the Paracels Islands most likely as a stop for their merchant fleet and to trade in the region. So they used to do what is called cabotage in maritime law, which is coastal trade. They used the Paracels Islands as anchor point, for their ships to trade. Vietnam could also claim that given the fact that since it was a French territory for some time, they could construct an argument saying that they are in fact the substitute State of France, and therefore they have a claim over the islands. But, this is far-fetched and Vietnam has not taken part that actively in the South China Sea case, because most likely they do not want to ruffle any feathers from China.

The Philippines are saying that they are geographically the closest to the islands and therefore given the proximity of their coast, the islands should be theirs. This is more or less the extend of their claim.

As far as Brunei and Indonesia go, they are interested parties.

- Relation in the region

Delphine Saint-Martin: On the dispute, the case that was brought up, what was the reaction of the other states that were not a party to the case?

Pierre Thévenin: First of all, the proceedings were first instituted in 2013 by the Philippines (plaintiff) against China (respondent). From that point onwards, China said that they were not going to appear in the proceedings, because they deemed that the arbitral tribunal is not competent to hear the dispute. So, they didn’t appear for the whole proceeding. They sent a few positions papers, so they objected to the jurisdiction of the tribunal. But they lost this, then they sent a paper saying that they did not accept this, and ultimately they did not accept the final award of the arbitral tribunal. They refused to comply with the decisions. Surely, they did not destroy their infrastructures of the artificial islands.

So, all the coastal states of the South China Sea case took part in a way in one way or another in the South China Sea case, as observers of the case. They submitted a few papers to express a point of view to the court throughout the case. Because you have to understand that if China had won the case if its activities over the Spratly Islands were legal then it would have had repercussions for Vietnam, Indonesia, and so on and so forth. With the case, Philippines’ claims have been in majority validated by the arbitral tribunal and so, all the coastal states in the South China Sea can refer to that decision if ever they have troubles with China. So, if China for example, starts building artificial islands on the Paracels Islands, Vietnam can say look there is the arbitral award from 2016 (South China Sea case) you cannot do that, it is illegal, and China knows it is not legal. So if you are a coastal state, you can use this decision as a lever to reinforce your position vis-à-vis China. That is why all the states were interested. Following this arbitration, however, China has not demolished the artificial islands it has built in the South China Sea.

On the substance of the South China sea case, the overall dispute on the South China sea is in part on the control of the islands, Spratly Islands and their nature, whether they are legally recognised as islands. This is because if the Spratly Islands are indeed islands then they are entitled to a territorial sea, a continental shelf and an EEZ, which is gives them a maritime expanse of up to 200 nautical miles, which is a very big area, especially in the South China Sea which is not that big (see picture 2). So it would have an impact on maritime boundaries of the region and also on the rights of the states to fish and exploit resources in the south china sea. This is because whoever is sovereign over the Spratly Islands, if indeed they are islands, can freely and fully exploit oil, gas and fish resources (see map 6). So, the first point was whether the Spratly Islands are islands, in fact the Court said that the Spratly Islands are not legally islands, from the point of view of the Law of the Sea Convention they are not islands. The Court said that some of them are above water at all times, but they cannot sustain human life on their own, so they are not islands. Referring back to the Law of the Sea Convention, in order for an island to be considered as an island it should be naturally formed, above sea level at all times, and able to sustain human life and economic activity (article 121 of the LOSC). So, the Court said that what China did is that they built an artificial island on a rock. The fact that China built an artificial island on a rock does not change the status of the rock. Even though they are augmented rocks, they still remain rocks and they are not islands. So they are not entitled to an EEZ, and continental shelf, to a 200 nautical miles maritime zone.

Delphine Saint-Martin: So, according to the law of the sea, this nine-dash line claim of China is not legal and even if China built these artificial islands to reinforce its claim, it is not legal, in conformity with the Law of the Sea.

Pierre Thévenin: Yes, you are right, according to the arbitral tribunal, this line dash line does not amount to sovereignty claim over the islands, despite what China has been arguing. The Tribunal has found that this nine-dash line opened historical rights for China, but the historical rights that China may have in virtue of its nine-dash line do not amount to a sovereignty claim. So the Tribunal basically said that there is a nine-dash line for China but it does not mean that China is sovereign upon the islands. This is because what the nine-dash line shows first and foremost is that China has used the South China Sea and the maritime expenses contained within the nine dashes, in virtue of this line, there might be specific fishing rights, in the EEZ of the neighbours, navigational rights, etc (see map 4 to 6). But it does not give enough ground to claim sovereignty upon the Spratly Islands.

- Arctic region

Delphine Saint-Martin: To move on to the Arctic, could you, please, explain what are the claims of the states in the region? What are their claims and what are the potential claims China is making in that region and what their interests are?

Pierre Thévenin: China tries to invest in the region, because it sees that it has economic potential, in the Northern Sea Route, through the Russian coast, or the North-West Passage, through the Canadian coast. China sees that these various Arctic routes might have future economic potentials (see map 7). However, China can not make any claims over the Arctic because it is not a coastal state of the Arctic. So China might attempt to claim that it has some kind of status, it has been publishing policy papers on the fact that China is nearly an Arctic State. But that does not open any right to China, not even to the Arctic Council. In this Arctic Council, there are only members that are Arctic States, such as Russia, the United States of America, Canada, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. Those are the only eight Arctic States which have voting rights in the Arctic Council and can influence policies in the Arctic Council. However, China can become an observer in the Arctic Council, as the European Union has done before. China has also been an observer since 2013. But that is the extent of the claim that China can make, not more than an observer to the Arctic Council.

The interests that exist in the Arctic region are economic for two reasons:

- shipping interests through the Northern Sea Route and North-West Passage

- exploitation of the continental shelf: the seabed of the coast of the Arctic States, there are more claims and dispute on that front

The interests in the region are mostly economic with a touch of environmental protection because nobody wants an oil spill in the Arctic.

Delphine Saint-Martin: Also, on the Arctic Council, you mentioned China is an observer to that council, and could you, please, explain what the role of the Arctic Council is and what China could do to influence the council as an observer?

Pierre Thévenin: The Arctic Council is an intergovernmental organization so it is an organization governed by the state parties. And in turn, you have the Arctic states that are president of the Arctic council and it is a form of cooperation. It was created in 1996 when the cold war had just barely finished and so every party involved was quite willing to have such an organization.

Regarding the Chinese way to influence the arctic council, they can revise proposed initiatives through papers where it expresses its point of view, concerns, ideas but that is only advice, and China cannot force the Arctic Council members to act upon it or draft a new treaty or launch a new program. However, China could gain influence upon certain members of the Arctic Council. We are talking about Russia’s and China’s relations in the Arctic. China is investing quite a lot in the Arctic. Frankly, I do not see any meaningful Chinese influence over Russia as far as the Arctic is concerned. Russia’s position on the Arctic is quite complex but ultimately they are too proud of their Arctic coast and the Arctic plays an important role in the Russian political discourse and in the wider Russian psyche and arts. So for China to influence the Russian political stance it would be quite difficult, especially if they go against Russia’s current position. What China could do is to influence a smaller member. For example, should Greenland become independent, it could via its investment in Greenland influence Greenland’s decisions. This is due to the fact that should Greenland become independent it would become a member of the Arctic Council. So, that is fiction but that is probably the only way they could influence an Arctic Council member.

Delphine Saint-Martin: On the environment and China’s position on the protection of the environment in the South China Sea and in the Arctic, and in general, would you have any details on the matter?

Pierre Thévenin: So global warming is bad and will carry nefarious effects for the region, but it will free up navigation in the Arctic Route. If there is less ice in the region, then the passage becomes freer. Therefore, more ships with fewer risks can sail through, which means more revenue. That is economically profitable for all States concerned. So there is a tension between environmental protection and commercial interest in the region. So far the transpolar Sea Route is not really a route, it cannot be used because there is too much ice at the moment. The Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage are not economically viable, in the sense that in the Northern Sea Route, only Russian ships sail through for economic purposes because they have to bring goods from point A to point B along the Russian coast. But only between 10 and 14% of the transit throughout the Northern Sea Route were actually foreign. It is not likely that it will develop quickly in the future because there is still too much ice.

To link this issue to the Middle East, Arctic shipping is in direct competition with the Suez Canal and the Persian Gulf. For example, if you measure the shipping time from Japan to Europe through the Suez Canal, which is currently the shortest way to link the two regions, it would take about one month to a month and a half. If you look at the same destination points but through the Arctic, the Arctic Routes are 20 to 30% shorter. If the Arctic navigation one day becomes a viable reality that everyone uses, that is used to a significant extent. It will bear important consequences because the Suez Canal and all the countries benefiting from the international navigation in the Persian Gulf and the middle east will suffer from it. It would no longer be the shortest route. In short, the Middle East, and Egypt first and foremost, will suffer if ever at some point the Arctic shipping routes are open and viable.

Map between the two routes: http://www.eiu.com/industry/article/591780243/the-northern-sea-route-rivalling-suez/2014-05-02

May 10, 2021

*Pierre Thévenin, Doctoral candidate at the University of Tartu (https://www.etis.ee/CV/Pierre_Thevenin/eng?tabId=CV_ENG)